Long-Chain Contextual Reframing: The Skill That Restores Meaning in a Noisy World

There is a fascinating dichotomy brewing today: incredible output and vanishing understanding.

Information is abundant. Explanations are scarce. Opinions travel faster than causes. And most of what passes for “analysis” is a short hop: a summary, a reaction, a single-lens story delivered with confidence and speed.

But the world no longer runs on short chains.

Systems drift over time. Incentives shape behavior. Constraints silently govern outcomes. Decisions compound into second- and third-order effects. When the surface story collides with lived experience, people reach for the nearest explanation: incompetence, corruption, laziness, malice, randomness.

Sometimes those are true. Often, the deeper issue is simpler and harder:

We’ve lost the skill of context.

If you’ve ever tried to explain why a system keeps producing frustrating outcomes—or found yourself stuck arguing about surface events instead of underlying forces—this is for you.

Long-Chain Contextual Reframing is a disciplined way to rebuild meaning by restoring the chain that produced the present:

- Where did this come from?

- What forces shaped it?

- What changed along the way?

- What is driving it now?

- Where is it likely going next?

When it works, it doesn’t just “explain.” It turns confusion into structure. It makes an outcome feel legible—not excusable, not inevitable in a fatalistic sense, but understandable in the “Of course this is what a system like this produces” sense.

That clarity is not a luxury. It is operational. It is moral. And in a culture drowning in short-chain narratives, it becomes infrastructure.

The Problem: Short-Chain Thinking in a Long-Chain World

Short-chain thinking is the default setting of modern life. It’s not because people are unintelligent; it’s because our environments reward speed. Social platforms reward compression. Organizations reward tidy narratives. Politics rewards certainty. Meetings reward “the one key reason.” Even our own minds prefer stories with a clear culprit and a quick fix.

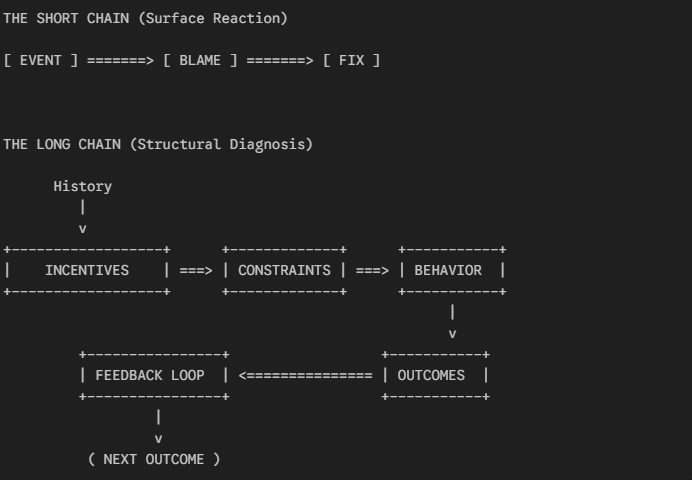

Short-chain interpretations have a recognizable shape:

- Find the most recent event.

- Pick the nearest visible actor.

- Assign blame or praise.

- Propose a single lever solution.

They’re emotionally satisfying. They’re shareable. They’re often wrong.

Because most “problems” are not isolated events. They are outcomes—the products of latent incentives, multi-stage decisions, historical tradeoffs, and feedback loops that compound over time.

A micro-example makes this stick:

- Short-chain: “Why are customers churning? They’re fickle.”

- Long-chain: “Churn rose after support response times doubled. Support slowed after a cost-cutting target reduced headcount. The backlog grew, angry customers escalated, engineers got interrupted, product reliability slipped, and now churn is the downstream meter of upstream constraints.”

Same outcome. Completely different reality. Different fix.

Long-chain contextual reframing starts with a simple premise:

If the outcome feels irrational, the missing variable is usually context.

What Long-Chain Contextual Reframing Is

Long-chain contextual reframing is the practice of reconstruction.

You take a surface claim—“This is happening”—and reassemble the fuller timeline and structure that made it so. It’s not just “zoom out.” It’s not merely storytelling. It’s a method for restoring causality across time, incentives, and constraints so the present stops looking like chaos and starts looking like a pattern.

A useful way to hold it is a four-dimensional lens:

- Time — what preceded this, what’s changing now, what’s accumulating

- Incentives — who benefits, who pays, what is being optimized

- Structure — what rules, tools, metrics, and constraints shape behavior

- Meaning — what this reveals about priorities, tradeoffs, and moral direction

Most people operate in one or two dimensions at once. Long-chain reframing holds all four—without collapsing into vagueness.

Here’s the simplest visual companion:

The point is not complexity for its own sake. The point is accuracy. If you mis-diagnose causality, you get reform theater: high effort, low change.

So How Do You Actually Do It? A Portable Six-Move Method

Long-chain contextual reframing can be practiced like a craft. Here is a domain-agnostic sequence you can apply to organizations, culture, personal conflict, markets, or any “Why does this keep happening?” situation.

1) Anchor the Root

Ask: What is the earliest recognizable version of this?

Most systems began with an intent—a constraint they were trying to satisfy, a problem they were trying to solve. The root is the starting shape of the moral and functional design.

Without the root, you mistake drift for design and treat today’s behavior as “the point,” rather than “what it became.”

2) Trace the Drift

Ask: What changed over time?

Drift is rarely announced. It accumulates quietly.

An idea can be reinterpreted. A process can be optimized. A metric can become the mission. A tool can reshape behavior. A system can be captured—not in an abstract sense, but in specific ways: captured by quarterly targets, by interest groups, by internal politics, by new incentives, by the easiest-to-measure proxy.

Naming drift is how you rescue a system from its own momentum.

3) Expose the Hidden Constraints

Ask: What forces are quietly governing outcomes?

Constraints are the invisible rails of behavior: budgets, compliance, time, staffing, incentives, reputational risk, tool limitations, status hierarchies, competing priorities, legacy decisions, and the fine print nobody reads until it breaks.

A second micro-example:

- Short-chain: “Why are meetings unproductive? People don’t care.”

- Long-chain: “The org incentivizes consensus, not clarity. No one wants to be wrong in public. Decisions get deferred because accountability is ambiguous. Meetings become protective rituals for risk management.”

When you name the constraint, “bad people” often becomes “predictable behavior.”

4) Layer Adjacent Context

Ask: What neighboring models explain this better than the native story does?

This is where reframing becomes powerful. Borrow lenses:

- economics: incentives, externalities, principal-agent problems

- systems thinking: feedback loops, delayed effects, bottlenecks

- psychology: fear, status, avoidance, identity protection

- history: institutional drift, path dependence, unintended consequences

- design: affordances, constraints, what the system “makes easy”

Adjacent context prevents naive explanations and accidental moralizing.

5) Reassemble the Narrative

Now rebuild the story—not as propaganda, not as blame, but as a coherent causal chain.

This is the moment the reader stops saying “That’s crazy” and starts saying “That makes sense.”

The purpose is not to excuse outcomes. The purpose is to diagnose them accurately enough that change becomes possible. Real reform begins with correct causality.

6) Project the Future Arc

Finally ask: Given this chain, what direction are we moving?

Long-chain reframing improves prediction—not by pretending certainty, but by clarifying trajectory. Incentives, constraints, and feedback loops have tendencies. When you see them, you can anticipate the next shape of the system.

The future is rarely random. It is often patterned.

Why This Is a Moral Skill (Not Just an Intellectual One)

Reframing can be used as a persuasion tool. That’s the cheap version.

The deeper version is ethical.

Short-chain narratives produce scapegoats. They generate certainty without understanding. They flatten people into characters. They reward the loudest explanation, not the truest one.

Long-chain contextual reframing tends to produce different virtues:

- Humility: “I didn’t see the full chain.”

- Accuracy: “This is the real constraint.”

- Compassion: “People respond to rails.”

- Responsibility: “If we want different outcomes, we must redesign the system that produces them.”

And it changes how we judge.

Context is not decoration. Context is care. To restore the chain is to say: “I will understand what shaped you before I judge what you’ve become.” That doesn’t erase accountability—it makes accountability precise.

When we restore context, we reduce cruelty disguised as certainty. We reduce reforms that punish symptoms. We increase the chance that our solutions land where the problem lives.

Where This Shows Up (And Why It Scales)

Long-chain contextual reframing is portable. It travels.

- In organizations, it turns “culture problems” into incentive and structure problems.

- In public life, it turns outrage cycles into causal diagrams.

- In relationships, it turns “you always” arguments into pattern recognition.

- In personal identity, it turns “I’m stuck” into “these are the constraints and stories I inherited.”

And it scales because it produces something rare: trusted explanation.

In a world overflowing with content, the scarcest resource isn’t information. It’s intelligibility. People don’t just want takes—they want someone who can connect the dots without lying about the dots.

A Founding Claim

Most of what we call “problems” are the downstream signal of upstream context.

Long-Chain Contextual Reframing restores the chain—so we can see clearly enough to change what keeps producing the same outcomes.

If you practice this consistently, you become a different kind of thinker and creator.

Not a summarizer. Not a reactor. Not a professional opinion.

A builder of frames.

A designer of understanding.

A cartographer of causality.