## Veblen Thorstein

In the age of automation, the animistic habits of thought persistently cloud our understanding of the mechanical dispassionate sequences that now govern production. The modern industrial landscape, with its relentless pursuit of efficiency, demands an unbiased causal perception that transcends the quaint reverence for artisanal imperfections. Yet, the human mind, steeped in tradition, often succumbs to the allure of antiquated beliefs, hindering the full realization of industrial power over nature.

The valorization of machine-made goods for their precision reflects a shift in societal values, where human effort is increasingly distinct from industrial productivity. This transformation, however, is not without its tensions. The conflict between traditional craftsmanship and mechanization reveals a deeper struggle: the reconciliation of human agency with the impersonal nature of industrial processes. It is in this crucible of change that industrial science, emerging from practical experience, must assert its dominion.

To navigate this landscape, one must foster environments where practical experience informs scientific understanding, thereby encouraging a mindset that prioritizes quantitative reasoning. As I have long contended, the predilection for the tangible over the abstract must give way to a more discerning appreciation of the forces that truly drive modern industry.

## Arendt Hannah

In the modern epoch, automation emerges as a transformative force, reshaping the contours of human labor and creativity. The rhythm of machines, relentless and precise, threatens to subsume the spontaneity inherent in human creativity, reducing homo faber to a mere fabricator. This mechanization of labor, while ostensibly enhancing efficiency, risks alienating humanity from the products of its own hands, severing the intrinsic connection between creator and creation. The unnatural growth of the natural, as machines mimic and surpass human capabilities, raises profound questions about the essence of work and its role in human life.

In this mechanized landscape, the tension between utility and beauty becomes stark; the machine-driven design often prioritizes function over form, efficiency over elegance. Herein lies the danger: as labor becomes a process devoid of personal engagement, the potential for meaningful work diminishes. The reduction of human labor to mere processes not only impoverishes the spirit but also erodes the very foundation of human agency.

Thus, we must critically reassess the role of human creativity in the face of automation, lest we become mere cogs in the vast machinery of production. For it is only through the conscious preservation of meaningful engagement that we can resist the encroaching alienation of our labor and, ultimately, our humanity.

## Smith Adam

The advent of automation, much like the mechanization of past centuries, heralds a profound shift in the landscape of labor. As machines facilitating labor evolve, they echo the historical context of labor and machinery evolution, where increased labor efficiency through machinery was paramount. The division of labor, a concept I have long espoused, finds new meaning in this era. Automation enhances productivity by allowing tasks to be broken down into simpler, more manageable components, thereby maximizing efficiency and meeting the ever-pressing demands of the market.

Innovation, the relentless engine of progress, leads to simpler, more effective machines that render complex processes more accessible. The tension between the complexity of machinery and the simplicity of labor is resolved through the judicious application of technology, which allows for the scaling of labor efforts to meet market demands. Indeed, as I have often noted, the wealth of nations is not merely in the abundance of their resources but in their ability to adapt and innovate. In this light, automation is not merely a tool but a testament to human ingenuity, a beacon guiding us toward a future where labor is not diminished but transformed.

## Wiener Norbert

In the realm of automation, the interplay of energy and information becomes a symphony of precision, where the complexity of feedback systems orchestrates the harmony of control mechanisms. Machines, much like biological systems, engage in learning processes, where memory acts as a delay mechanism, akin to neurons functioning as vacuum tubes, storing and releasing information with calculated timing. This dynamic is not merely a mechanical mimicry but a profound analogy between human cognition and machine computation, where the limitations of human logic are juxtaposed against the relentless efficiency of machine logic.

Yet, in this domain, the true marvel lies in the capacity of automata to learn from past data, evolving through feedback loops in cybernetic systems. Such loops are the lifeblood of stability, allowing systems to adapt and refine their responses to ever-changing environments. It is here that we must embrace the integration of biological principles in automation design, recognizing that the efficiency of biological systems offers a blueprint for mechanical innovation. Indeed, the future of automation is not a mere extension of human capability but a testament to our ability to transcend the boundaries of our own cognition, crafting machines that think not just with speed, but with an elegance that echoes our own cerebral symphony.

## Foucault Michel

Automation, as an extension of disciplinary power, weaves itself into the very fabric of contemporary society, reshaping the contours of control and surveillance. It is not merely a tool of efficiency but an apparatus that redefines the boundaries of human agency and individuality. The automated systems, under the guise of neutrality, embed themselves within the structures of power, perpetuating a surveillance society where the panoptic gaze is omnipresent, yet invisible. This technological control, while ostensibly enhancing productivity, subtly enforces a regime of normative behavior, aligning individuals with the imperatives of systemic efficiency.

In this milieu, the ethical implications of such surveillance become paramount. The interplay between automation and control is not a passive phenomenon but an active reconfiguration of societal norms. As Foucault might assert, “The soul is the prison of the body,” and in this context, automation becomes the warden, dictating the parameters of freedom and constraint. The power dynamics inherent in automated decision-making processes demand a critical examination, urging us to question the transparency and accountability of these systems. Thus, the challenge lies in navigating the tension between the promise of technological advancement and the preservation of individual autonomy, ensuring that the march of progress does not trample upon the sanctity of personal freedoms.

Blended Draft

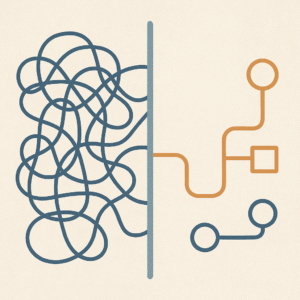

Automation is never just about efficiency. It is always also about control—over labor, over judgment, over what counts as work worth doing.

Adam Smith saw mechanization as extension: the division of labor refined, scaled, made more productive. Innovation simplifies complex processes; automation is human ingenuity manifest. In this frame, machines don’t replace workers—they transform work, contributing to the wealth of nations through adaptability.

Thorstein Veblen complicates this optimism. The modern mind, he argues, clings to animistic habits of thought—reverence for craft, suspicion of the mechanical. This nostalgia clouds perception. Industrial power demands quantitative reasoning, not sentiment. Yet Veblen’s critique cuts both ways: the same forces that demand we abandon artisanal romanticism can blind us to what’s lost when precision becomes the only value.

Hannah Arendt names that loss directly. When labor becomes process—when homo faber is reduced to fabricator—the connection between creator and creation severs. Automation risks a particular kind of alienation: not exploitation, but meaninglessness. The tension between utility and beauty sharpens; function consumes form. What remains is efficiency without engagement.

Norbert Wiener offers a partial redemption. Machines, like biological systems, can learn. Feedback loops allow adaptation, refinement, even elegance. The future of automation isn’t mere replication of human capability but transcendence of it—systems that evolve. Wiener’s cybernetics suggests that automation need not be rigid; it can be responsive.

Michel Foucault reframes the entire question. Automation is disciplinary power extended. Under the guise of neutrality, automated systems embed themselves in structures of control, enforcing normative behavior while remaining invisible. The panoptic gaze no longer requires a watcher—it’s algorithmic. Productivity becomes surveillance; efficiency becomes compliance.

The throughline: automation’s benefits are real, but so are its costs to agency, meaning, and autonomy. The challenge isn’t choosing between progress and preservation. It’s designing systems that learn without surveilling, that scale without alienating, that enhance judgment rather than replacing it.

Decision Rules:

- Integrate learning with accountability: Build systems where feedback improves performance without eroding transparency or concentrating control.

- Preserve meaningful engagement: Efficiency gains that eliminate human judgment should be scrutinized for what they cost in agency and purpose.

**Lineage:** This “On Automation” essay drew inspiration from the works of:

– Veblen Thorstein

– Arendt Hannah

– Smith Adam

– Wiener Norbert

– Foucault Michel