Graeber David

Debt is not merely an economic transaction; it is a moral narrative woven into the fabric of society, shaping identities and dictating destinies. Historically, societies have recognized the corrosive potential of debt, instituting cycles of jubilee to reset the scales of obligation and restore communal balance. Yet, in modern times, the market-state symbiosis has transformed debt into a mechanism of control, where the individual is shackled by the invisible chains of financial obligation. This transformation is not just a shift in economic practice but a profound alteration in the moral landscape, where debt is often perceived as sin, a mark of personal failing rather than a structural inevitability.

The dichotomy between individualism and collective obligation reveals itself starkly in the cultural narratives surrounding debt. In a world where personal freedom is exalted, the burden of debt becomes a silent tyrant, dictating choices and constraining possibilities. As Graeber might argue, the moral imperative is clear: to reassess and dismantle the structures that perpetuate debt as an instrument of exploitation. By understanding debt’s historical context, we can advocate for systems that prioritize forgiveness and equity, recognizing that true freedom lies not in the absence of obligation but in the equitable distribution of responsibility.

Weber Max

Debt, in its most profound sense, is a moral burden that transcends mere financial obligation, echoing the transactional nature of our relationship with the divine. The ledger of God’s book-keeping, where every action is meticulously recorded, parallels the human compulsion to balance accounts, both spiritual and material. This compulsion is not merely a reflection of economic necessity but a manifestation of the tension between traditional religious values and emerging capitalist practices.

Historically, the evolution of usury laws has mirrored society’s struggle to reconcile the moral indifference of wealth with the ethical imperatives of justice and punctuality. These laws, once stringent in their prohibition of interest, gradually adapted to the demands of a burgeoning capitalist economy, illustrating the conflict between religious doctrine and financial practices.

Yet, as we navigate this landscape, we must recognize that debt is not merely a financial transaction but a moral contract. The sentence that could only be written by Weber Max: “In the calculus of salvation, the soul’s ledger is balanced not by gold but by grace, a currency beyond the reach of earthly creditors.” Herein lies the challenge: to balance business interests with ethical considerations, lest we become morally bankrupt in our pursuit of material gain.

Tocqueville Alexis de

In the annals of governance, debt emerges not merely as a financial instrument but as a profound reflection of a nation’s character and moral compass. The historical context of debt reveals its foundational role in shaping the contours of statehood, where the moral weight of debt bears heavily upon the conscience of a nation. In the American experiment, the constitutional framework intricately weaves debt obligations into the fabric of governance, underscoring the inextricable link between debt and the very essence of democratic responsibility.

Debt, in its essence, is a testament to the nation’s promise—a promise not only to its creditors but to its own citizens, who must bear the consequences of fiscal imprudence. The tension between state and federal debt responsibilities further complicates this landscape, as the balance of power and duty must be meticulously maintained to prevent the erosion of national unity. It is here that one discerns the moral implications of incurring debt, where the specter of obligation looms large over the republic.

In the words of Tocqueville, “The measure of a nation’s greatness is not in its wealth but in its ability to honor its debts with integrity and foresight.” Thus, debt becomes a mirror, reflecting the virtues and vices of a people, demanding both accountability and prudence in its stewardship.

Chanakya

Debt, like the shadow of a towering tree, casts its presence over the debtor, binding them in an obligation that demands honor. In the realm of finance, where the exchange of promises is as common as the exchange of coins, the recovery of debts must adhere to strict rules and timelines, lest chaos ensue. Judicial oversight serves as the vigilant guardian, ensuring that the scales of justice do not tip unfavorably against either party.

Interest rates, the silent arbiters of financial transactions, fluctuate based on the nature of the agreement and the standing of those involved. It is imperative that these rates align with legal standards, for unchecked greed can turn the wheels of fortune into the chains of servitude. Pledges and collateral, the tangible assurances of repayment, must be managed with care, safeguarding the interests of both debtor and creditor.

As Chanakya would counsel, “A debt left unaddressed is a serpent in the grass, poised to strike when least expected.” Therefore, clear terms must be established at the onset of any debt agreement to forestall future disputes. In the intricate dance of obligation and repayment, wisdom dictates the path to harmony.

Nietzsche Friedrich

In the labyrinth of human morality, debt emerges not merely as an economic transaction but as a primordial force shaping the moral landscape. The consciousness of guilt, a specter haunting the debtor, is a testament to the transformation of personal relationships into moral obligations. This metamorphosis, where the intimate becomes the obligatory, reveals the historical evolution of debt as a foundational concept in morality. Here, the creditor and debtor engage in an eternal dance, a societal structure where freedom is shackled by obligation.

The debtor’s burden is not just financial but a psychological yoke, a weight that bends the spine of the soul. The moralization of debt, often sanctified by religious frameworks, transforms it into an existential condition, where suffering becomes the currency of repayment. It is in this crucible of obligation that punishment emerges as a form of retribution, a grim ledger where suffering compensates for transgressions.

Yet, one must ask: is not the sanctity of debt a mere construct, a relic of slave morality that binds the spirit? In challenging these chains, we confront the paradox of freedom—freedom that is both the origin and the end of all moral inquiry. Thus, the debtor’s plight is a mirror reflecting the tension between the will to power and the shackles of inherited guilt.

Blended Draft

Debt is never merely owed. It is narrated—moralized, politicized, internalized until the ledger becomes identity.

David Graeber locates debt’s power in this moralization. Historically, societies recognized its corrosive potential, instituting jubilees to reset obligation and restore balance. But modernity inverted the frame: debt became personal failing rather than structural condition. The invisible chains of financial obligation now dictate choices, constrain possibilities, and shackle freedom under the guise of responsibility. Graeber’s imperative is clear—dismantle the systems that weaponize debt, and recognize that equity lies not in the absence of obligation but in its just distribution.

Max Weber extends the moral dimension into the spiritual. The ledger of God’s bookkeeping parallels our compulsion to balance accounts, both material and divine. Usury laws evolved as society struggled to reconcile wealth’s indifference with justice’s demands. Debt is not transaction but contract—and the soul’s balance is measured in grace, not gold.

Alexis de Tocqueville scales the question to nations. Debt reflects a people’s character: their capacity for prudence, their willingness to honor promises. In the American experiment, fiscal obligation is woven into governance itself. A nation’s greatness lies not in wealth but in its ability to honor debts with integrity. The specter of obligation looms over republics as surely as individuals.

Chanakya offers the pragmatist’s counter: debt is shadow, binding debtor to creditor in an arrangement demanding clear terms, judicial oversight, and timely resolution. A debt unaddressed is a serpent in the grass. Wisdom lies in structure—rules that prevent chaos, rates aligned with law, collateral managed with care.

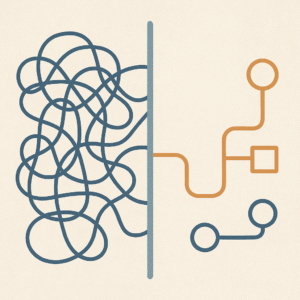

Friedrich Nietzsche cuts deepest. Debt is primordial—guilt made flesh, the transformation of relationship into obligation. The debtor’s burden bends the spine of the soul. Suffering becomes currency; punishment becomes repayment. But Nietzsche asks: is the sanctity of debt anything more than slave morality dressed in contract law? To challenge debt’s moralization is to confront the paradox of freedom itself.

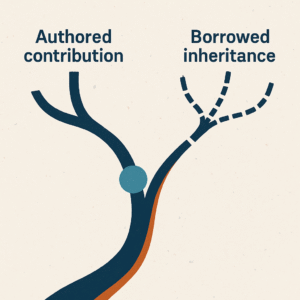

The throughline: debt operates simultaneously as economic instrument, moral narrative, political bond, and psychological weight. Systems that treat it as purely transactional miss its grip on identity. Systems that moralize it without structural reform perpetuate exploitation. The challenge is designing arrangements where obligation serves relationship rather than replacing it.

Decision Rules:

- Recognize debt’s moral dimension without weaponizing it: Distinguish structural conditions from personal failing. Jubilee logic—periodic reset, equitable distribution—remains relevant.

- Establish clear terms and oversight: Ambiguity breeds exploitation. Governance of debt requires transparency, timeliness, and accountability to both parties.

Lineage: This “On Debt” essay drew inspiration from the works of:

- Graeber David

- Weber Max

- Tocqueville Alexis de

- Chanakya

- Nietzsche Friedrich