I didn’t know the phrase “adversarial interoperability” when I started building Policy Vault.

I just knew that drug coverage rules were hard to find.

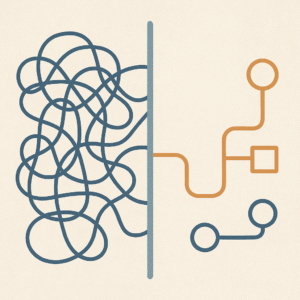

They lived behind an endless click maze: portals inside portals, gated access, PDFs buried in repositories, dead links that somehow stay “official,” breadcrumb trails that make you feel like you’re the problem for wanting to understand your own coverage. The criteria existed in public, but not in a way that made them reachable.

And that’s the first thing people miss:

In modern systems, availability is not access.

A document can be “public” and still be functionally private.

Cory Doctorow gave me language for what I’d been doing: build a new product or service that plugs into an existing one without permission from the company that controls the chokepoint. He calls that adversarial interoperability.

I’m not borrowing his term as a gimmick. I’m borrowing it because it names a moral move that has been hiding in plain sight:

When incumbents capture value through opacity, the ethical response isn’t always to ask nicely.

Sometimes the ethical response is to build the interface they refused to build.

The UI is the policy

We pretend policy is the PDF. It’s not.

Policy is the lived experience of finding it, interpreting it, complying with it, contesting it.

If the criteria are buried, then burial is part of the policy.

If the language is elastic, then elasticity is part of the policy.

If no one can reliably tell you which system a prior auth is supposed to go through—payer portal, PBM portal, EHR-integrated path, vendor middle-layer—then the uncertainty is part of the policy.

The user interface is governance.

And in drug coverage, the interface is often a deliberate narrow passage: it preserves a kind of network advantage—not the big, dramatic monopoly story, but the quieter regional one. The advantage of “we know where the documents live.” The advantage of “we know which form counts.” The advantage of “we know how to speak this dialect.”

Opacity doesn’t just slow people down. It assigns power to whoever has the map.

Right to Repair wasn’t about tractors. It was about control.

If you want the cultural parallel that makes this click, it’s Right to Repair.

That’s the name of the push you’re thinking of—the fight over car parts, diagnostic software, phones, and “parts pairing” in devices like iPhones.

It’s not a settled issue. It’s active.

- In January 2025, the FTC and multiple state attorneys general sued John Deere, arguing that repair is being steered back into Deere’s authorized dealer network through controlled tools and software. The company makes “the only fully functional software repair tool capable of performing all repairs”—and limits it to dealerships.

- Oregon’s Right to Repair law took effect January 1, 2025, and it’s notable because it restricts “parts pairing”—the practice of using software locks to make replacement parts not work unless the manufacturer blesses them.

- More than a dozen states introduced right-to-repair agricultural equipment legislation in the first two months of 2025 alone.

Here’s the ethical core of Right to Repair:

If you own the thing, you shouldn’t need permission to maintain the thing.

If the manufacturer’s moat is “only we can access the diagnostic truth,” then making diagnostics available is not aggression—it’s agency restoration.

Drug coverage has the same shape.

Patients “own” the consequences. Employers “own” the premiums. Clinicians “own” the time cost. But the interpretive tools—the map of what’s required, what’s covered, what’s contested, what changed since last year—are scattered into a maze that mostly benefits insiders.

When the maze itself is the moat, a clean response is to build a door.

The consumer protection principle no one’s applying to drugs

The FTC spent years fighting “dark patterns”—design choices that make enrollment easy and cancellation deliberately hard. The principle they landed on is simple: the process for opting out must be at least as easy as the process for opting in.

Amazon paid $2.5 billion for violating this. Their crime wasn’t fraud—it was asymmetric friction. Easy to join Prime. An uncomfortable click maze to leave.

That principle has a name now: Click to Cancel. It’s being applied to subscriptions, streaming services, gym memberships—anywhere the business model depends on people not being able to exit cleanly.

But drug coverage?

No one’s applying the principle there.

| Domain | Dark pattern | Regulatory response |

| Subscriptions | Easy to enroll, hard to cancel | FTC Click to Cancel |

| Farm equipment, cars with electronic components, iPhones | Easy to buy, impossible to repair | Right to Repair laws, FTC lawsuit |

| Drug coverage | Easy to deny, hard to understand | Nothing yet |

The asymmetry is the same. The friction is the same. The beneficiaries of confusion are the same.

Policy Vault is what happens when you apply the Click to Cancel principle to coverage criteria:

The process for understanding your coverage should be as easy as the process for being denied. The process of taking your money should be as easy as utilizing the benefit.

The CMS rule left drugs out. That matters.

This is where the stance gets sharper, and I’ll keep it honest:

CMS has been pushing payer interoperability and prior authorization modernization through the Interoperability and Prior Authorization Final Rule (CMS-0057-F)—FHIR APIs, data access, more process visibility.

But prescription drugs are explicitly excluded from that push. CMS excluded drugs from the Prior Authorization API and related process requirements. It also excluded drug prior auth from the new requirement to add prior auth info into the Patient Access API.

CMS’s stated reasoning is that drug prior auth standards, processes, and timeframes differ from medical services. That explanation may be administratively true.

But the signal is still worth naming:

The lane with the highest volume of daily friction—drug access—remains structurally safer for opacity.

And payers are taking the hint. According to recent industry surveys, 45% of payers now say they will not include drugs in the prior authorization API—up from 26.5% previously. The exclusion isn’t just regulatory cover. It’s becoming standard practice.

I’m not saying there’s a smoke-filled room. I’m saying: when a paradigm persists, it’s usually because it serves someone’s incentives. And in pharmacy benefit land, there are plenty of actors who profit from uncertainty:

- From time costs

- From abandonment (the “walk-away rate”)

- From patients failing to persist through appeals

- From clinicians absorbing admin burden

- From employers not having clean explanations, comparisons or alternatives

- From the public being unable to audit what “medical necessity” means in practice

A system doesn’t need villains to protect opacity.

It just needs momentum.

I’m not here to be a standards evangelist

Let me say this cleanly: I’m not here to tout FHIR, HL7, Da Vinci, or any of the alphabet soup that keeps healthcare’s plumbing from collapsing.

Standards matter. But standardization can also become a delay tactic—endless “stakeholder alignment” while the asymmetry persists in plain sight.

And this is where adversarial interoperability becomes a real ethic instead of a techy flex:

You don’t wait for permission to make public rules usable.

You don’t ask the maze for directions.

You build a parallel lane.

Policy Vault: a third-party interface to drug coverage reality

Policy Vault runs counter to a simple claim:

You can’t keep calling it “public criteria” if it takes twenty minutes and a pilgrimage through broken portals and links to find it.

So I brute-forced the problem. Not as performance—out of contact. Out of friction. Out of the repeated experience of watching people with real needs bounce off a maze designed for no one’s understanding.

Policy Vault takes coverage criteria that already exist “out there” and makes them:

- Searchable (not scavenger-hunt-able)

- Comparable (not one-PDF-at-a-time)

- Diffable (so drift becomes visible)

- Citable (so conversations can anchor to receipts)

This is not “hacking.” It’s not stolen data. It’s not proprietary leakage.

It’s an alternative end user client for the coverage reality of millions of Americans.

I think of my approach as a principled dig:

You did the work to make this slightly legible. Nice.

I’m taking it all the way.

Because if we have nothing to hide, a better interface shouldn’t threaten us.

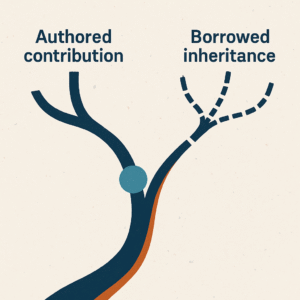

The line between extraction and contribution

There’s one constraint that keeps this from turning into a power fantasy:

I’m not trying to become a new gatekeeper. I’m trying to make gatekeeping harder.

That’s the difference between extraction and contribution.

Extraction takes value and leaves the system weaker, less legible, more confused.

Contribution takes what already exists and makes it more walkable, more usable, more contestable.

Contribution means provenance matters. Versioning matters. Context matters. You don’t bend meaning for convenience. You don’t launder ambiguity into certainty. You don’t “summarize” your way into propaganda.

You make the pathway walkable—and you leave markers so other people can check your work.

That’s the ethic.

The posture

Adversarial interoperability is what you invoke when the system’s moat is confusion and the public consequences are real.

Right to Repair asked for the tools to fix what you own.

Click to Cancel demanded that exit be as easy as entry.

Policy Vault is the same posture, adapted to healthcare:

If the rules govern your care, you deserve a way to see them—clearly, quickly, and without asking permission from the people who benefit when you don’t.

And if that makes someone uncomfortable, I have a sincere question:

What do you have to hide?