Health plans and pharmacy benefit managers must make a structural choice that sounds boring until you’re the one trying to use it: Do you put an entire drug class in one policy—or do you give each drug its own document?

Cystic fibrosis (CFTR) medications make the trade-off obvious. Kalydeco, Orkambi, Symdeko, Trikafta, Alyftrek—all “same neighborhood,” but not the same street.

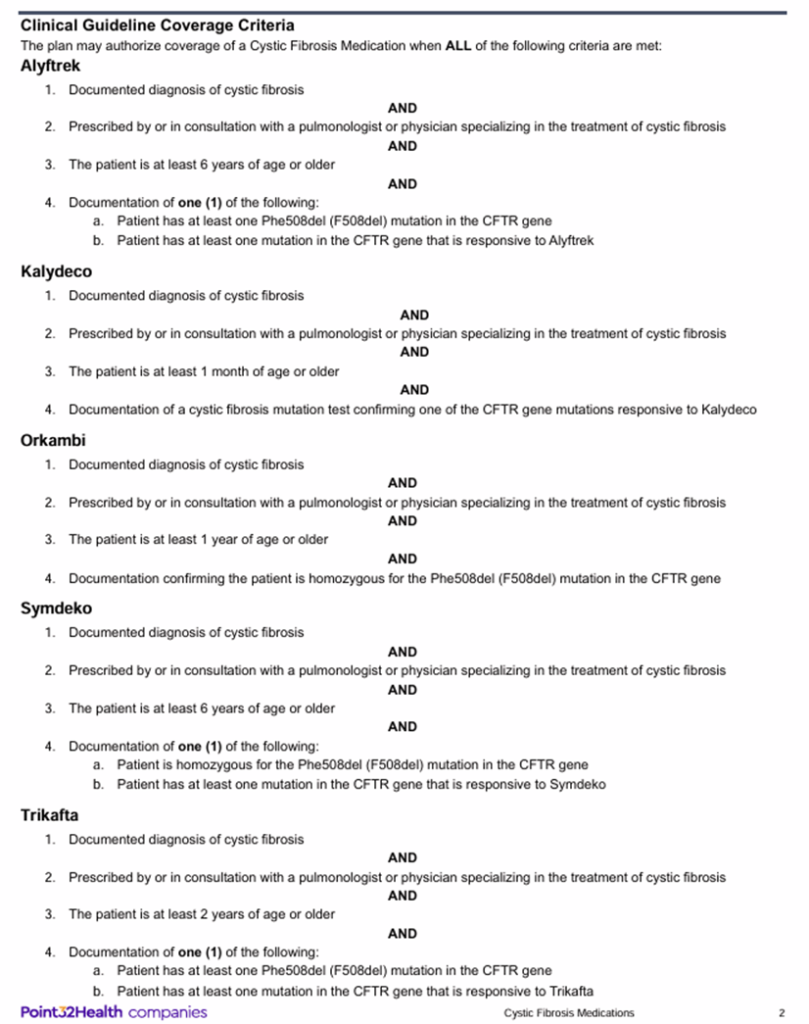

Here’s Point32Health’s class policy for CF medications. One document, five drugs, branching eligibility, relatively clean:

· Plan: Point32Health (Harvard Pilgrim Health Care / Tufts Health Plan)

· PBM: OptumRx

· Line of business: Commercial

· Drug class: Cystic Fibrosis Medications

· Effective date: June 1, 2025

· Accessed: January 7, 2026

Same therapeutic intent. Different age floors. Different genotype gates. The clinical reality is a branching tree, not a single line.

Class-Based Policies

One document for the whole landscape

What they’re good for:

- Clinical completeness. One-stop shop. If you’re thinking “CFTR modulator for this patient,” you can see the whole menu in one place.

- Discoverability of alternatives. If the drug you had in mind doesn’t fit, you might notice an adjacent option—without having to know it exists ahead of time. I’m sure seasoned Pulmonologists would know better, but maybe useful for a resident, or mid-level provider.

- Consistency for the plan. One document, one set of overarching, shared conventions. Fewer opportunities for contradictory language across drugs.

What they cost:

- Administrative burden. The prescriber (or pharmacist) must parse the document to find the specific branch that matches the patients needs.

- Hidden precision. A drug can be “covered” but functionally buried—present in the PDF, absent in the prescriber’s working memory.

- Interpretive drift. Class policies often inherit templated clauses that add indirection (“per labeling,” “per criteria,” “per guideline”) rather than collapsing the answer into something direct and actionable.

Individual Drug Policies

One document per medication

What they’re good for:

- Precision of lookup. If your question is “Can I get Alyftrek?” you don’t want a scavenger hunt. You want a straight answer, and fast.

- Cleaner PA workflows. The request is drug-specific, the policy is drug-specific, the documentation checklist is tighter.

- Lower cognitive load. Fewer branches. Less interpretation. Less room for “I missed the one section that mattered.”

What they cost:

- Alternative blindness. If you don’t already know the other options, you don’t go looking. The structure quietly reduces clinical discoverability.

- Maintenance complexity. More documents to author, update, version, and keep consistent—more surface area for drift from the operations side.

The Unresolved Tension

If class policies optimize for landscape visibility, and individual policies optimize for lookup precision, the real question becomes: is this something that requires standardizing?

A 9-month-old with CF and a Phe508del mutation isn’t eligible for Orkambi (age floor: 1 year). But they are eligible for Kalydeco—if the prescriber knows to look or request. In a class policy, that’s discoverable. In an individual drug policy world, it requires knowing what you don’t know.

Meanwhile, a prescriber requesting Alyftrek for a 5-year-old is going to hit a wall (age floor: 6 years). In an individual policy, that’s immediately clear. In a class policy, it’s paragraph four, subsection (a), after you’ve already started the PA work.

The failure modes look a little different. Neither is eliminated by structure alone.

The Layer That Makes It Irrelevant

A data layer can answer the only question that matters in the moment: “What’s available for THIS patient?”—regardless of how the plan stored the underlying policies.

Patient age, genotype, diagnosis → eligible options. No parsing. No scavenger hunt. No alternative blindness.

That’s what I’m building toward with Policy Vault. Not advocacy for one structure over the other—just collapsing the indirection so the answer shows up when it’s needed.

The Question I’d Leave You With

If you live inside these structures daily—as a prescriber, pharmacist, PA processor, benefits analyst, charge nurse—which failure mode hurts more?

Missing the alternative you didn’t know existed? Or wasting time parsing a document for an answer that should have been immediate?

I genuinely want to know.