How pharmacy benefits actually work—without spin.

TL;DR

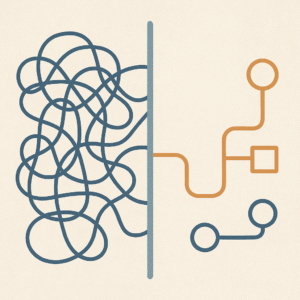

Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) sit in the middle of a complex, pooled‑risk system. Their job is to turn messy drug markets and clinical guidelines into something that looks like a predictable benefit: formularies, tiers, copays, prior auth, and edits that run in milliseconds at the pharmacy counter.

From an employer seat, that system often feels opaque or adversarial. You see denied claims, confusing tiers, GLP‑1 drama, and year‑over‑year cost increases that don’t always match what you’re told. The intent behind much of this architecture is good—stewarding limited dollars, managing risk, nudging toward value—but the impact is uneven and rarely explained.

This guide walks through what PBMs actually do, how formularies and coverage rules really work, where employer misunderstandings come from, and what questions you can ask to design a smarter, more transparent benefit. It’s foundational on purpose—lightly technical, payer‑side honest, and focused on making the “invisible architecture” legible so you can make better decisions for your members.

1. Why Employers Feel in the Dark

If you’re sponsoring a pharmacy benefit—self‑funded, level‑funded, or via a fully insured arrangement—you’re paying for a system that often feels like a black box:

Members get denied and complain to HR.

GLP‑1s show up as massive line items.

Formularies change midyear.

Brokers repeat a small set of talking points.

Your reports show “savings,” but your total spend still creeps up.

It’s not that people are hiding everything from you (though opacity exists). It’s that the underlying machinery was never designed to be explained to you clearly. PBM contracts, policy drafting, pricing files, and prior auth logic evolved as operational plumbing, not as a transparent teaching object.

Here’s the truth:

PBMs are not purely villains, and they’re not pure saviors.

They’re stewards of pooled risk with mixed incentives and accumulated complexity.

The architecture they run—formulary tiers, clinical criteria, edits—is meant to solve real problems, but often does it in ways that are hard to inspect.

This guide aims to do one simple thing:

Give you a structural understanding of how pharmacy coverage is built, operated, and updated—so you can ask better questions and negotiate from a position of clarity.

2. The Core Function of PBMs: Managing Pooled Risk

At its simplest, a PBM is a risk and operations translator:

On one side: volatile drug prices, clinical nuance, specialty launches, GLP‑1 demand spikes, new oncology regimens, safety signals.

On the other: an employer who wants predictability—stable premiums, managed trend, consistent access, and fewer unwelcome surprises.

2.1 What “Pooled Risk” Actually Means

Health plans and self‑funded employers are exposed to tail events:

A handful of gene therapy claims.

A cluster of high‑cost oncology cases.

A wave of GLP‑1 utilization driven by social media.

On a person‑by‑person basis, that’s chaotic. Across a population, it becomes a distribution: you can estimate what’s likely to happen in aggregate, even if you can’t predict any one member’s outcome.

PBMs sit here:

Aggregating lives across many employers and plans.

Standardizing coverage approaches (to a point).

Smoothing volatility through contracts, networks, and utilization rules.

The business language is “trend management” and “drug spend control.” The underlying mechanism is turning chaos into something actuarially tractable.

2.2 Why That Matters to You

If you’re a sponsor, you are effectively saying:

“I’m willing to pay a PBM to turn uncertain, spiky drug claims into a managed, somewhat predictable cost curve—using tools I don’t have time or expertise to build.”

That’s the core value proposition. Everything else—rebates, formularies, prior auth, edits—is implementation.

Seeing PBMs as pooled‑risk managers doesn’t excuse everything they do. But it does reframe the system from “random denials” to “the architecture they assembled to manage uncertainty.”

3. Formulary Logic: The Real Reason Drugs Are Tiered

Formularies look simple on the surface:

Tier 1: Lowest copay (usually generics)

Tier 2: Preferred brands

Tier 3+: Nonpreferred brands / specialty

Sometimes: carve‑out tiers, non‑formulary, or exclusions

To an employer or member, it can feel arbitrary:

“Why is Drug A preferred, but Drug B—same class—isn’t?”

3.1 What a Formulary Actually Does

A formulary is a choice architecture for prescribing and dispensing:

Clinical: Align with guidelines (e.g., ADA, ACC/AHA, NCCN).

Economic: Lean toward drugs that deliver value per dollar spent.

Operational: Limit the number of competing products per niche so rules stay manageable.

A simplified way to think about it:

A formulary is a ranked shortlist of “acceptable default choices” for each condition, with cost and evidence baked into the ranking.

Tiering is the visible part. The invisible part is the decision logic that determined which drug landed where.

3.2 How Drugs Get Placed

In a decent setup, tiering decisions reflect:

Clinical efficacy and safety (head‑to‑head or class‑level).

Total cost of care impact (not just unit price).

Contract terms (rebates, guarantees, price protections).

Utilization patterns and adherence data.

Employer and population needs (e.g., GLP‑1 appetite, high‑risk conditions).

In a worse setup, tiering is skewed toward:

The largest short‑term rebate checks.

Contracts that offload risk in ways that look good on paper but feel bad in practice.

“Revenue first, outcomes later” approaches.

Most formularies sit somewhere in between. Intent is often good. Impact is mixed.

3.3 Why Formularies Differ Across Plans

Employers often ask:

“Why does Carrier X cover Drug Y but Carrier Z doesn’t—or puts it on a worse tier?”

Because:

Each PBM has different aggregate contracts.

Different populations generate different utilization and rebate patterns.

Different P&T committees make slightly different clinical tradeoffs.

Some employers carve out (or in) certain classes or adopt custom exclusions.

From your vantage point, it’s inconsistency. From theirs, it’s local optimization over a messy landscape.

4. How Clinical Policies Are Built & Updated

Behind every prior auth form, step‑therapy sequence, or “this drug is non‑formulary” message sits a clinical policy. That policy didn’t appear from nowhere; it moved through a lifecycle.

Understanding that lifecycle is key if you ever want to:

Challenge a decision.

Ask for a rationale.

Negotiate something that actually sticks.

4.1 A Simplified Policy Lifecycle

Most coverage changes follow a predictable path:

Market surveillance → P&T agenda

New drugs, new indications, safety warnings, price changes, new evidence.Policy drafting & internal review

Pharmacists and clinicians update criteria, indications, step logic.Committee approval (P&T or similar)

Formal vote, recorded rationale (at least internally).Operational codification

Turning prose criteria into actual rules, PA questions, and edits.Testing & sign‑off

Ensuring rules match clinical intent—at least for known scenarios.Production release & communication

Pushing rules to portals, claim systems, and public policy PDFs.

If you trace artifacts at each step, you get a provenance trail from “here’s the FDA label and guidelines we saw” to “here’s why your member was rejected at the pharmacy counter.”

Most employers never see that trail. But it exists, and it’s where you can ask higher‑quality questions:

“What evidence did you use to tighten this GLP‑1 criterion?”

“When did this policy version go live for our group?”

“How is renewal logic actually coded in your PA system?”

4.2 Text vs. Implementation

One of the biggest hidden gaps is:

The PDF says one thing. The code does something slightly different.

Reasons:

Criteria are written in narrative sentences.

Operational systems need explicit, yes/no logic.

Ambiguities get resolved on the fly.

Edge cases get handled differently by different analysts.

You can have three problems simultaneously:

Clinical mismatch: Implementation doesn’t match committee intent.

LOB divergence: Commercial vs. Exchange vs. Medicare handled differently.

Version drift: Portal screenshots, PDFs, and claims logic out of sync.

From your perspective, it looks like inconsistency or unfairness. From inside, it’s often just complex systems with incomplete traceability.

5. How Coverage Rules Actually Work: Branching Logic & Criteria Thresholds

When you hear “prior auth criteria,” think branching logic, not vibes.

A simple coverage rule might look like this under the hood:

To approve Drug X for Condition Y, we need:

A = Diagnosis is confirmed.

B = Baseline lab indicates severity above a threshold.

C = Member has tried appropriate first‑line therapy.

Translated into logic:

IF A (diagnosis confirmed)

AND B (lab ≥ threshold)

AND C (documented trial of first‑line therapy)

THEN approve for 6 months

ELSE deny or route to “eligible for exception review.”

5.1 Example: GLP‑1 Initial Approval (Simplified)

For an adult with type 2 diabetes (T2D), a policy might say:

Age ≥ 18

Diagnosis of T2D

Trial of at least one or two oral agents

A1c above a certain threshold within the last 90 days

In logic‑ish form:

IF age ≥ 18

AND trial_of_orals_met (e.g., metformin 90 days in last year)

AND A1c ≥ 7.0% within last 90 days

THEN approve GLP‑1 for 6 months

The engine is always:

Atoms: individual checks (age, BMI, lab, diagnosis, prior meds).

Logic: how those checks are combined.

5.2 Why This Matters to Employers

When you hear:

“We tightened GLP‑1 criteria.”

What that really means is:

One or more thresholds changed (e.g., A1c moved from 7.0% to 7.5%).

Time windows narrowed (lab within 60 days instead of 90).

Step therapy was added or reordered.

Renewal requirements increased (e.g., requiring a certain weight loss or A1c reduction).

Those changes have measurable impact:

Who can start treatment.

Who can stay on treatment.

How many appeals you’ll see.

How many members churn off therapy.

When you understand coverage as branching logic instead of “PBM mood,” you can ask:

“Which criteria changed, and by how much?”

“What scenarios get denied now that were approved last quarter?”

“How are we tracking the outcomes of these thresholds on our population?”

6. What PBMs Actually Do Behind the Scenes

To make all this work at scale, PBMs run a large amount of operational machinery employers rarely see.

Here’s a non‑exhaustive list of functions that sit under the pharmacy benefit hood.

6.1 Core Operational Functions

Eligibility management

Who is covered, under which plan, with which effective dates.Claim adjudication

Real‑time “yes/no/what tier/what copay/what accumulators” logic at the point of sale, in ~200–500 milliseconds.Formulary and price file maintenance

Updating NDCs, MAC lists, ingredient costs, pharmacy network rates.Clinical rule deployment

Prior auth logic, step therapy, quantity limits, age edits, duplication checks, DAW codes, prescriber networks.Drug utilization review (DUR)

Screening for interactions, duplicate therapy, dose ranges, contraindications.Fraud, waste, and abuse detection

Pattern detection for suspect claims, prescriber outliers, pharmacy anomalies.Member and provider portals

Making coverage information, formulary lookup tools, and PA submissions accessible (in theory).Reporting and analytics

Employers see the surface of this: dashboards, high‑cost claimants, category spend, snapshot P&T updates.

6.2 Why This Matters

Most of the time, this machinery is invisible, and that’s good—it means things are working. You notice it only when:

A clinically sound claim gets denied.

A policy changed and no one told you.

Costs jump in a category you thought was under control.

A member becomes a Twitter or Facebook case study in coverage frustration.

Behind each of those moments is a chain of:

Surveillance → Policy drafting → Logic implementation → Testing (or not enough) → Release → Communication (or lack of it)

Your job as a sponsor isn’t to run this machinery yourself. But understanding that it exists—and that it can be interrogated—is essential.

7. Intent vs. Impact: How Incentives Shape Coverage

Most PBM professionals you’ll meet are not trying to harm patients or trick employers. The intent behind many rules is:

Preserve access for high‑value therapies or effective alternatives.

Prevent clear misuse or low‑value use.

Keep premiums and contributions somewhat affordable.

Yet you see:

Members stuck in appeal loops.

Clinically sound requests denied on technicalities.

GLP‑1 criteria that feel misaligned with guideline reality.

Drugs that seem clinically similar placed on very different tiers.

That’s the intent vs. impact gap.

7.1 Where Incentives Come From

PBMs are influenced by:

Rebate and discount structures

Volume‑based agreements with manufacturers.Administrative fee models

How they get paid by plans and employers.Guarantee contracts

Promised trend, unit costs, or rebate returns.Operational cost constraints

How many people they can staff to review, code, and test policies.Regulatory pressure

State and federal requirements, audits, CMS rules.

None of these are inherently bad. But they create pressure gradients, and those gradients bend decisions.

7.2 Employer‑Side Consequences

From where you sit:

A “cost‑saving” step therapy rule may actually increase downstream medical costs.

A tight GLP‑1 policy may reduce drug spend but increase long‑term cardiometabolic risk.

A design meant to steer to “best net cost” may accidentally favor a drug that’s harder to adhere to.

The important shift is this:

Don’t assume malice. Don’t assume purity.

Assume architecture shaped by incentives—some visible, some not.

Your role is to surface those incentives and decide which ones you’re willing to live with.

8. Common Employer Misunderstandings (and Straight Answers)

Let’s address a few patterns that consistently show up in employer conversations.

8.1 “Why Does Prior Authorization Exist at All?”

It’s not just gatekeeping. PA exists to answer questions like:

Is this drug being used for an evidence‑based indication?

Are there safer or more cost‑effective options that should be tried first?

Does this member meet criteria where the risk/benefit balance makes sense?

Done well, PA can:

Prevent obvious misfires (wrong dose, wrong indication).

Nudge toward first‑line options.

Surface documentation that genuinely matters for clinical monitoring.

Done badly, it becomes:

Friction for friction’s sake.

A way to covertly offload cost without accountability.

A barrier to high‑value therapy.

As an employer, your question isn’t “PA or no PA?” It’s:

“Where do we want PA to protect us, and where is it hurting our members?”

8.2 “Why Do Formularies Differ So Much?”

Because:

Contracts differ.

Population risk differs.

Evidence interpretation differs.

Risk appetite differs.

You’re not crazy to feel whiplash when one PBM treats Drug X as “must have” and another treats it as “nice to have.” But instead of asking, “Why don’t they agree?”, ask:

“What clinical and economic rationale is each using?”

“Which rationale aligns with our population and values?”

8.3 “Why Do Coverage Criteria Change Midyear?”

Because the world changes midyear:

New evidence appears.

New drugs launch.

Safety signals emerge.

Manufacturer strategies shift.

Budget pressure intensifies.

In a perfect world, criteria would only change in clear, well‑announced cycles with full rationale. In reality, change is often:

Batched around P&T meetings.

Partly reactive.

Communicated unevenly.

Your lever: require version transparency:

“When did criteria last change?”

“What changed?”

“What impact did you model for our group?”

8.4 “Why Do Denials Happen When Members ‘Seem to Qualify’?”

Because coverage is determined by:

What’s written and what’s documented and what’s submitted.

Time windows and thresholds.

How the rule is coded.

A member may “in reality” qualify, but:

Required lab isn’t in the record.

Documentation doesn’t show the prior trial.

Time window is slightly off.

An implementation bug or mis‑routing exists (wrong criteria or wrong drug requested).

This doesn’t make the member’s frustration less real. But it does suggest a different class of solutions:

Documentation support.

Better PA form design.

Tighter testing of rules.

Clear exception processes.

9. The Economics of Pharmacy Benefits (Foundational Only)

You don’t need a 200‑slide deck on rebate algebra. You do need a few core mental models.

9.1 Gross vs. Net

Gross cost: What a drug “costs” on a public list.

Net cost: What you pay after discounts and rebates.

PBM talk often lives in the gross/net distinction:

Some drugs look expensive but net out lower due to rebates or special cost‑savings programs.

Others look cheap but net out higher when you account for utilization rate, specialty markups, or poor adherence.

9.2 Spread and Admin Models (Very High Level)

You’ll see arrangements like:

Spread pricing: PBM keeps the difference between what they pay pharmacies and what they bill you.

Pass‑through + admin fee: You pay closer to the true underlying cost plus an explicit admin fee.

Each has tradeoffs. The point isn’t to endorse a model here, but to note:

The way your PBM gets paid will influence how aggressively they engineer your formulary and PA criteria.

9.3 Category‑Level Impact

Instead of obsessing over unit prices, focus on:

Total category spend (e.g., GLP‑1s, inflammatory biologics, oncology).

Per‑member‑per‑month (PMPM) trends for those categories.

Utilization patterns (new starts, persistency, dose escalations).

Downstream effects (hospitalizations, ER visits, key lab metrics when available).

The right question to your PBM:

“Show me how this coverage design impacts total cost of care and key outcomes for our population, not just drug spend in isolation.”

10. What PBMs Don’t Tell Employers (But Should)

There are things that aren’t stated plainly in most employer decks—not out of malice, but because they’re uncomfortable or complex.

10.1 Formularies Are Not Static

They evolve constantly. If your understanding is based on a one‑time grid, you’re missing the story.

What you should get instead:

Version history of key classes (e.g., GLP‑1s, oncology).

Change logs with effective dates and high‑level rationale.

10.2 Coverage Criteria Are Not Standardized

Two plans can quote the same guideline but implement it differently:

Different A1c thresholds.

Different trial length for step therapy.

Different renewal criteria.

You should know:

Where your plan sits relative to “typical” implementations.

Whether your population is being held to stricter or looser criteria—and why.

10.3 Implementation Is as Important as Policy Text

The PDF might look reasonable. The rules might behave differently.

PBMs rarely walk employers through:

How criteria get translated into actual PA questions and adjudication rules.

How edge cases are handled.

How they test for misalignment between text and code.

You’re allowed to ask:

“Show me how this GLP‑1 policy behaves in real test cases.”

“Walk me through denial and approval scenarios.”

10.4 “Preferred” Doesn’t Always Mean Clinically Best

“Preferred” might mean:

Clinically similar + economically advantaged, or

Economically advantaged with clinically acceptable tradeoffs.

You don’t have to micromanage every class. But in high‑impact categories, you can ask:

“What tradeoffs did you consider to call this ‘preferred’?”

“What happens to adherence and outcomes in real‑world data?”

11. How Employers Can Actually Improve Their Pharmacy Benefit

You can’t rewrite the entire system. But you can pull very real levers.

11.1 Clarify Your Population and Priorities

Before arguing about a single drug, answer:

What are our top 3–5 clinical risk areas? (e.g., diabetes, cardiovascular disease, inflammatory conditions)

Where are we seeing avoidable ER visits or admissions?

Where do members feel the most friction?

Use that to focus your attention:

You don’t need to deeply interrogate every antibiotic.

You probably should interrogate GLP‑1 criteria, inflammatory biologics, and key chronic disease drugs (this ends up falling neatly into the 80/20 rule).

11.2 Ask for Policy Transparency in Key Classes

For your top risk categories, ask your PBM to provide:

Current criteria text (initial and renewal).

A plain‑language explanation of each criterion.

A few representative approval and denial scenarios.

Any planned changes in the next 6–12 months.

You’re not micromanaging; you’re aligning.

11.3 Focus on Thresholds and Windows, Not Slogans

The real levers are often small numbers:

A1c ≥ 7.0 vs. 7.5 (could disqualify hundreds or thousands of individuals from coverage access).

60‑day trial vs. 90‑day trial of a first‑line drug.

5% weight loss vs. 10% for renewal.

Authorization duration of 6 months vs. 12 months.

When those numbers move, people’s lives change.

Ask:

“Which thresholds are we using?”

“What would happen if we adjusted them toward guideline norms?”

“How many members would be impacted by a softer or stricter threshold?”

11.4 Align PA With Documentation Reality

If every GLP‑1 denial is “missing documentation,” you don’t just have a member problem—you have a design problem.

Work with your PBM to:

Ensure PA forms ask for data that exists and is accessible.

Reduce free text where possible.

Consider pre‑check approaches for large groups of members.

Goal: friction where it actually protects value, not where it creates random administrative burden.

11.5 Build Feedback Loops

Most employers treat pharmacy coverage as a once‑a‑year negotiation topic. That’s not enough.

Consider:

Quarterly check‑ins on 2–3 key classes.

A simple “coverage friction report” from HR and member support.

Joint reviews of appeals and exceptions to spot patterns.

You don’t need a 50‑page deck—just enough visibility to see where architecture is misaligned with your goals.

12. The Future of Drug Coverage (Foundational Forecast)

You’re not signing up to become a coverage engineer. But the tools and primitives underneath drug coverage are changing.

12.1 From Narrative PDFs to Machine‑Readable Criteria

Over time, policies will look less like:

“For initial approval, member must have tried X, Y, and Z…” (buried on page 7 of a PDF)

and more like:

Explicit, structured rules with simpler designs, provenance, and perhaps API endpoints.

Clear thresholds and time windows.

Versioned logic that can be queried and compared.

For employers, this means:

Easier comparisons across plans.

Easier detection of silent criteria changes.

Better alignment between coverage design and your values.

12.2 More Transparent Linkage to Outcomes

Expect increasing pressure to show that:

Tightening criteria doesn’t just save money, but preserves or improves outcomes.

Loosening access in certain areas yields downstream benefits.

That’s where value‑based thinking and coverage architecture intersect. Not as a buzzword—just as a better feedback loop.

13. Closing: Understanding as the First Act of Stewardship

As an employer or benefit buyer, you sit closer to the people affected by these decisions than anyone else in the chain:

You see their complaints.

You hear the stories HR hears.

You’re responsible for both the dollars and the trust.

PBMs are, in many ways, running necessary infrastructure. They absorb volatility, implement complex guidelines, negotiate pricing, and manage a staggering amount of operational detail.

But the fact that something is complex doesn’t mean it has to be opaque.

The first act of stewardship is understanding:

How pooled risk works.

What formularies and clinical criteria are really doing.

Where intent diverges from impact.

Which thresholds and rules matter most for your population.

Once you see the architecture, you don’t have to accept every default. You can:

Elevate your inquiries.

Push for better alignment with clinical reality.

Design a pharmacy benefit that treats members as people, not just cost centers.

And if you want help translating coverage rules into something your team can actually reason about—line by line, threshold by threshold—I build tools and frameworks for exactly that.

Sometimes the most powerful change isn’t a new product. It’s a clearer lens on the system you already fund.

Want Clearer Answers on Pharmacy Benefits?

If you’d like help understanding coverage criteria, redesigning your formulary logic, or navigating GLP-1 or specialty drug decisions, feel free to reach out. I work with employers and benefit buyers who want clarity, alignment, and practical insight.