Professionals are trained into competence before they’re trained into consent.

You learn how to be dependable. How to be sharp on demand. How to answer quickly, sound composed, carry weight without flinching. You learn the choreography of being useful.

And then—quietly—you notice the cost: you can be highly functional while inwardly absent. You can do everything asked of you and still feel like no one actually met you in the work. Competence becomes a cover for disappearance.

Self-accord is the refusal to let that happen.

It isn’t authenticity as performance. It isn’t moral purity. It’s not a personal brand. It’s an internal agreement you keep renegotiating: the terms under which you will show up, the price you will pay, the kind of life you’re building through your commitments.

I don’t experience disaccord as a philosophy problem first. I experience it as a body report.

A lump in the throat when I’m about to say yes to something I don’t mean. A dullness where curiosity used to be. The strange sensation of watching myself work from across the room—like my hands are doing the task while my mind has stepped back, quietly unwilling to co-sign the reason.

Those signals aren’t melodrama. They’re instrumentation. They are the earliest evidence that I’m becoming unhomed inside my own effort.

The culture trains you to override them.

“Be responsive.”

“Be a team player.”

“Just jump on for five minutes.”

“Are you available right now?”

That last one is the cleanest tell. Not because urgency is always fake—sometimes it’s real—but because urgency is often manufactured: urgency used as a shortcut to authority. The moral frame becomes: if you were good, you’d be reachable. If you were serious, you’d be interruptible. If you were committed, your mind would be on-call.

But some kinds of thinking—and some kinds of honesty—require long, unbroken stretches. Not because you’re precious, but because shallow time creates shallow agreement. The deeper parts of you don’t show up in five-minute increments. They arrive slowly. They need quiet. They need permission to be unfinished.

Self-accord is what you protect so that your work doesn’t become a polished surface with no person behind it.

A useful definition is negative: self-accord is what remains when competence stops compensating for misalignment. It’s the difference between being impressive and being intact.

And you can test for it without mysticism.

Look for three signs: friction, cost, surprise.

Friction is where reality resists you. The edge case that breaks the neat explanation. The constraint that refuses your preferred story. The part that won’t compress into something clean. If nothing resists you—if everything is smooth—there’s a chance you’re operating at the level of arrangement rather than encounter.

Cost is what you had to give up to remain honest. Sometimes it’s time. Sometimes it’s the pleasant illusion of being universally liked. Sometimes it’s the habit of constantly proving yourself. Cost is not a badge; it’s a receipt. It tells you whether you’re in relationship with what you’re doing, or merely managing appearances.

Surprise is the moment the work changes you. Not in a dramatic conversion story—more like a small internal shift: I didn’t know I believed that until I wrote it. I didn’t see that pattern until I touched the actual surface. Surprise is evidence you’re not just rehearsing.

This is where many smart people get trapped: they consume frameworks like cooking shows—satisfied by watching, but starving. They never stand at the stove.

Self-accord brings you back to heat.

It asks you to stop living as a spectator to your own potential. Not through hustle. Through contact. But contact has a shadow side.

When you’re highly competent, you can carry things you have no business carrying. You can sustain a misalignment for years simply because you’re strong enough to bear the weight. You can become the person who absorbs the chaos, fills every gap, answers every ping. Your capability makes it look like everything is fine.

But the opposite of accord isn’t just “too much.” It’s dissipation—a fracture of attention and intent. Commitments multiply without being chosen. Work becomes scattered. You remain functional while becoming a stranger to your own fatigue. You keep moving, but you stop arriving.

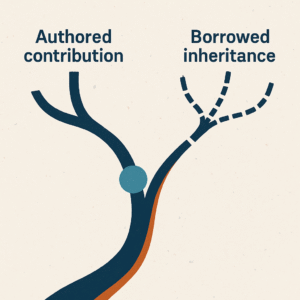

So the work of self-accord is not to do less for the sake of doing less. It’s to do what you do with authorship.

To insist that your obligations are not merely inherited.

To insist that your time is not merely extractable.

To insist that your mind is not merely available—treated as a public utility.

This is where the practice matters—not as a life hack, but as training: a weekly ritual strong enough to keep you intact.

Once a week, create one protected block—thirty minutes is enough. Longer is better. Treat it like a private appointment with the part of you that cannot speak in meetings.

In that time, choose one real surface you touched this week—something you couldn’t learn secondhand. Sit with it until the urge to perform fades.

Write what resisted. Not what you “think about it,” but where reality pushed back. Where your assumptions broke. Where your confidence thinned. Where your attention tried to flee.

Name the cost you’re paying—especially the quiet ones. The hidden tax of being reachable. The tax of being agreeable. The tax of being the one who “can handle it.”

Then leave one proof of life: a single sentence that only a human in contact with the world could write. A sentence that shows a person was here—not a machine, not a persona, not a performer. A sentence that tells the truth about what you saw.

Do that for four weeks and you’ll notice the shift. Not necessarily more done. Something better: more presence. More coherence. Less borrowed posture. A clearer internal yes. A cleaner no.

Self-accord isn’t a mood. It’s maintenance.

It’s how you keep your competence from becoming a disguise.

It’s how you steer clear of identity debt.

It’s how you remain inside your own work.